Can AI really predict tomorrow’s stock price?

In this hands-on case study, I put a lightweight neural network to the test using none other than NVDA, the tech titan at the heart of the AI revolution. With just five core inputs and zero fluff, this model analyzes years of stock data to forecast next-day prices — delivering insights that are surprisingly sharp, sometimes eerily accurate, and always thought-provoking. If you’re curious about how machine learning can be used to navigate market uncertainty, this article is for you.

Are humans naturally drawn to those who claim to foresee the future?

Astrology, palmistry, crystal balls, clairvoyants, and mystics — all have long fascinated us with their promise of prediction. Today, Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML) seem to be the modern-day soothsayers, offering insights not through intuition, but through data and mathematics.

With that playful thought in mind, I asked myself: How well can a lightweight neural network forecast tomorrow’s stock price? In this article, I build a simple, no-frills model to predict NVDA’s next-day price — using only essential features and avoiding any complex manipulations

I’ve been fascinated by the challenge of predicting NVDA’s stock price for the next day. For one, it’s an incredibly volatile stock — its price can swing wildly, almost as if someone sneezed down the hallway! What’s more impressive is that in November 2024, NVIDIA briefly became the most valuable company in the world, reaching a peak market cap of $3.4 trillion.

NVDA has captured the imagination of those driving the AI revolution, largely because its GPU chips are the backbone of modern AI/ML models. So, testing my neural network on NVDA’s price movement felt like a fitting experiment — whether the model forecasts accurately or not.

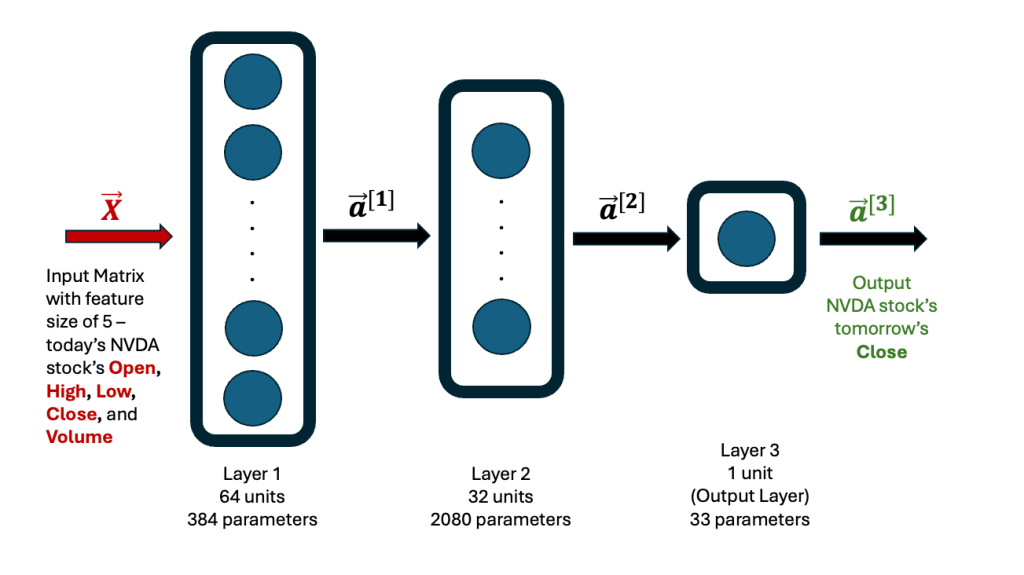

My neural network model takes in just 5 features per data point — the stock’s end-of-day Open, High, Low, Close, and Volume — to predict tomorrow’s Close price.

For training, I used NVDA’s stock data from January 1, 2020, to December 31, 2024 — a five-year period that includes 1,258 trading days. The target variable is the known next day’s Close price. The core idea was simple: Given today’s stock metrics for NVDA, can we predict tomorrow’s Close price?

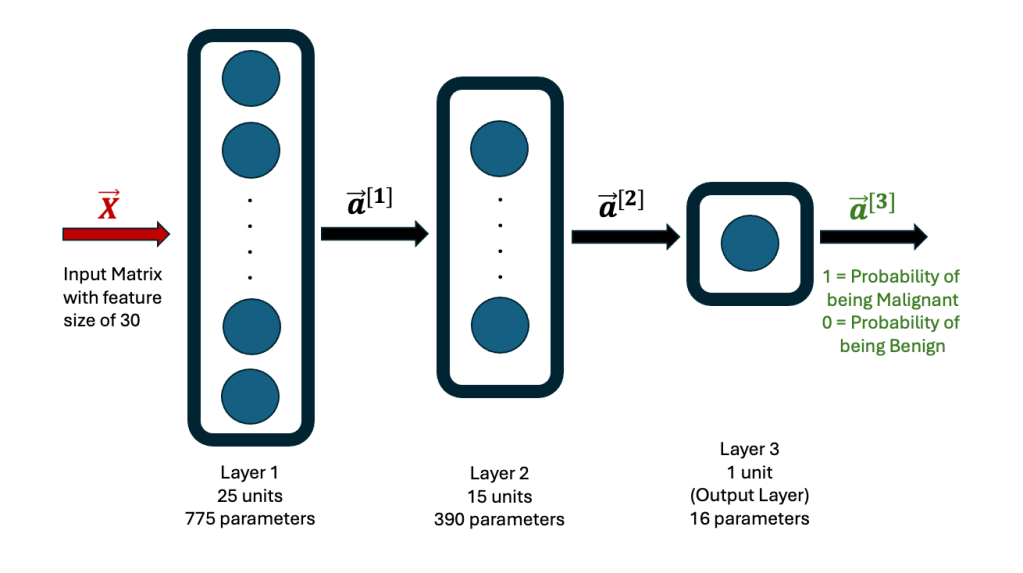

The basic architecture of the neural network is a schema I’ve used many times before, and I’ve shared it here for clarity.

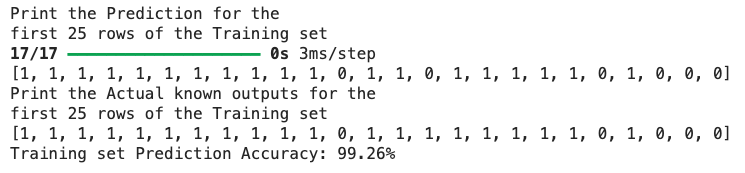

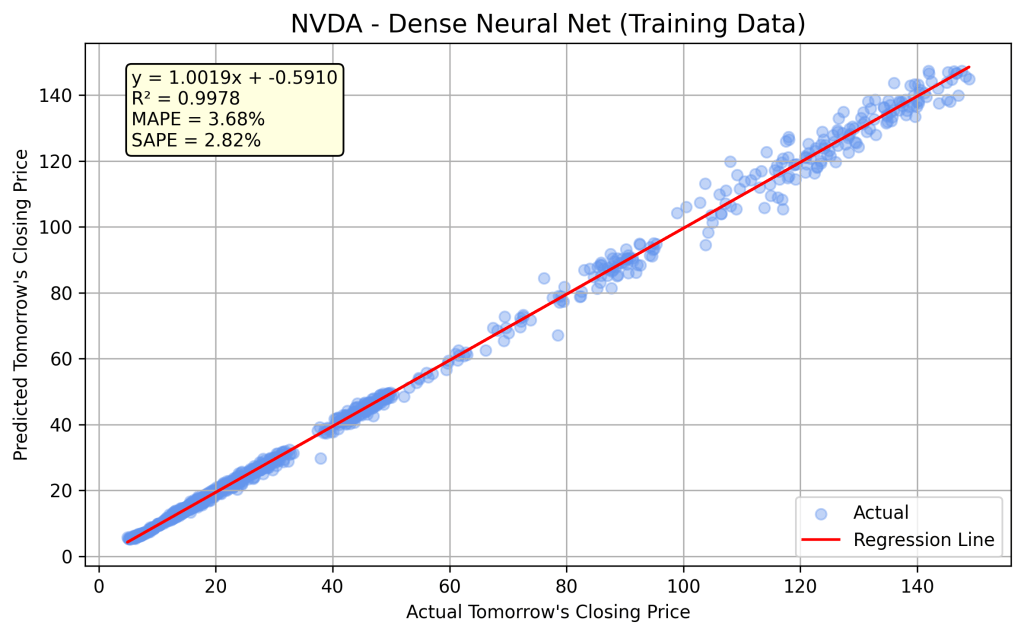

After training, the model learns all its weights and biases, totaling 2,497 parameters. It’s always a good idea to validate predictions made by a newly developed model — by running it on the training data and comparing the results with actual historical data. The graph below illustrates this comparison. The linear regression fit between the actual and predicted Close prices is excellent (R² = 0.9978). MAPE refers to the Mean Absolute Percentage Error, while SAPE is the Standard Deviation of the Percentage Error.

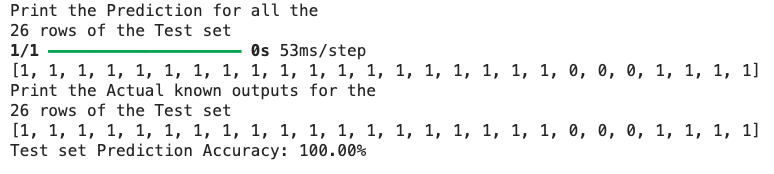

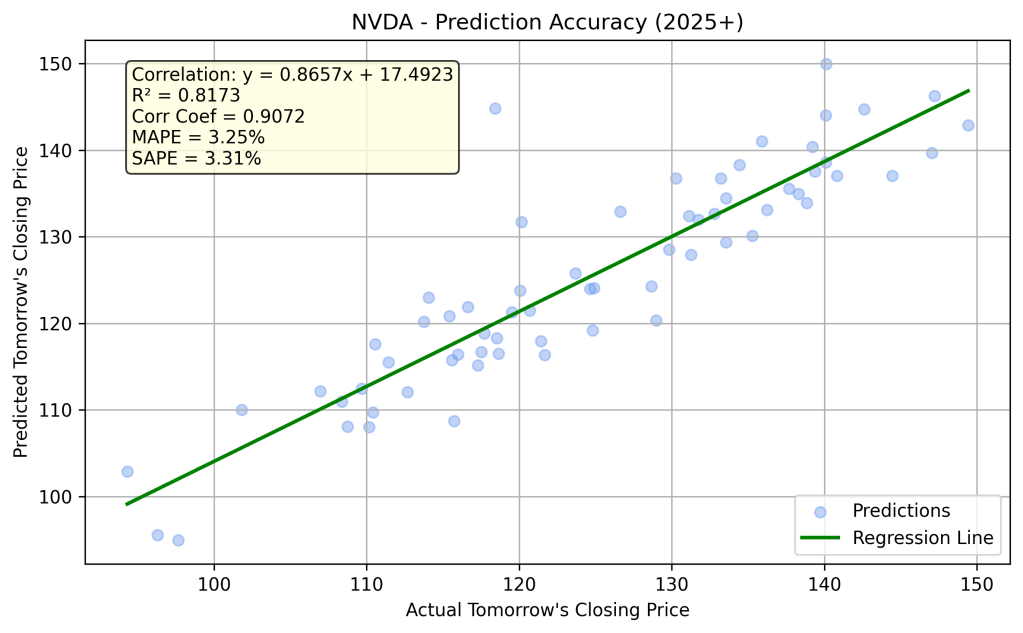

The trained model is now ready to predict NVDA’s closing price for the next trading day, based on today’s end-of-day data. I ran the model for every trading day in 2025, up to the date of writing this article: April 9, 2025 (using the known Close from April 8, 2025). The linear relationship between the actual and predicted Close prices for this period is shown in the following chart.

The correlation is reasonably strong (R² = 0.8173), though not as high as the model’s performance on the training set. On some days, the predictions are very accurate; on others, there are significant deviations. You’ll appreciate this better by examining the results in numerical and tabular form. The table below is a screenshot from the live implementation of the model, which you can run and explore on the Hugging Face Spaces platform. Update – please see a refined implementation at MLPowersAI, where you can see next day predictions for 5 stocks (AAPL, GOOGL, MSFT, NVDA, and TSLA).

The wild swings in closing prices — as reflected by large percentage errors — are mostly driven by market sentiment, which the model does not account for. For example, on April 3 and 4, 2025, the prediction errors were influenced by unexpected trade tariffs announced by the U.S. Government, which triggered strong market reactions.

Even though the percentage error swings wildly in 2025, we can still derive valuable insights from this lightweight neural network model by considering the MAPE bounds. For example, on March 28, 2025, the actual Close was $109.67, while the predicted Close was $113.11, resulting in a -3.14% error. However, based on all 2025 predictions to date, we know that the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) is 3.25%. Using this as a guide for lower and upper bounds, the predicted Close range spans from $109.47 to $116.76.

We observe that the actual Close falls within these bounds. I strongly recommend reviewing the current table from the live implementation to make your own observations and draw conclusions.

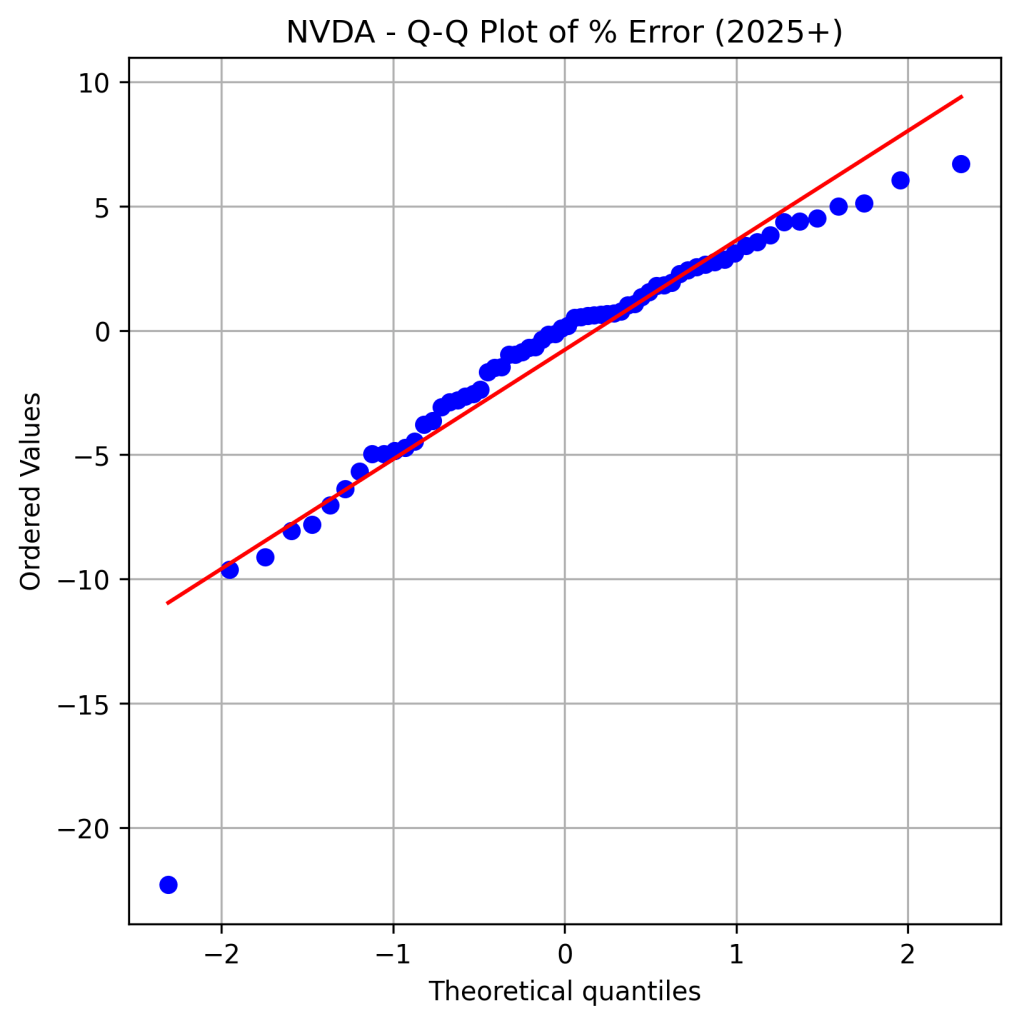

I was also curious to examine the distribution of the percentage error — specifically, whether it follows a normal distribution. The Shapiro-Wilk test (p-value = 0.0000) suggests that the distribution is not normal, while the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test (p-value = 0.2716) suggests that it may be approximately normal. The data also exhibits left skewness and is leptokurtic. The histogram and Q-Q plot of the percentage error are shared below.

Another way to visualize the variation between the actual and predicted Close prices in 2025 is by examining the time series price plot, shown below.

Closing Thoughts …

Technical traders rely heavily on chart-based tools to guide their trades — support and resistance levels, moving averages, exponential trends, momentum indicators like RSI and MACD, and hundreds of other technical metrics. While these tools help in identifying trading opportunities at specific points in time, they don’t predict where a stock will close at the end of the trading day. In that sense, their estimates may be no better than the guess of a novice trader.

The average U.S. investor isn’t necessarily a technical day trader or an institutional analyst. And no matter how experienced a trader is, everyone is blind to the net market sentiment of the day. As the saying goes, the market discounts everything — it reacts to macroeconomic shifts, news cycles, political developments, and human emotion. Capturing all that in a forecast is close to impossible.

That’s where neural network-based machine learning models step in. By training on historical data, these models take a more mathematical and algorithmic approach — offering a glimpse into what might lie ahead. While not perfect, they represent a step in the right direction. My own lightweight model, though simple, performs remarkably well on most days. When it doesn’t, it signals that the model likely needs more input features.

To improve predictive power, we can expand the feature set beyond the five core inputs (Open, High, Low, Close, Volume). Additions like percentage return, moving averages (SMA/EMA), rolling volume, RSI, MACD, and others can enhance the model’s ability to interpret market behavior more effectively.

What excites me most is the democratization of this technology. Models like this one can help level the playing field between everyday investors and institutional giants. I foresee a future where companies emerge to build accessible, intelligent trading tools for the average person — tools that were once reserved for Wall Street.

I invite you to explore and follow the live implementation of this model. Observe how its predictions play out in real time. My personal belief is that neural networks hold immense potential in stock prediction — and we’re only just getting started.

Update (May 2025):

Since publishing this article, I have deployed a more advanced neural network model that forecasts next-day closing prices for five major stocks (AAPL, GOOGL, MSFT, NVDA, TSLA). The model runs daily and is hosted on a custom FastAPI and NGINX platform at MLPowersAI Stock Prediction.

Disclaimer

The information provided in this article and through the linked prediction model is for educational and informational purposes only. It does not constitute financial, investment, or trading advice, and should not be relied upon as such.

Any decisions made based on the model’s output are solely at the user’s own risk. I make no guarantees regarding the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the predictions. I am not responsible for any financial losses or gains resulting from the use of this model.

Always consult with a licensed financial advisor before making any investment decisions.